L ARGE AND leaky, India's lockdown became "localised" this week. In the parts of the country hit hardest by covid-19, restrictions remain. Elsewhere, they have been largely relaxed. People can visit places of worship, but cannot touch idols. They can go outside to shopping malls, but not the gaming arcades or cinemas inside. In Punjab, mall-goers can buy clothes but cannot try them on first.

The lockdown, which began on March 25th, has failed to stop the virus—the caseload continues to grow alarmingly. But it has succeeded in halting the economy. The number of people in work fell to 282m in April, compared with an average of over 400m last year, reckons the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy ( CMIE ), a research firm, which asks people if they were employed that day (unlike the official data, which ask if people were employed at any time that week).

Many things are taking place:

Free exchange - Economic research documents black Americans' struggle for equality | Finance

Many black Americans left in search of opportunity. Over the 20th century a Great Migration unfolded, in which millions of black families left the South for northern cities. Movement began in earnest during the first world war, when northern manufacturers' demand for labour soared and the flow of immigrants from Europe was interrupted. Employers began to recruit in the South. Some black workers followed family members up north.

The response to black migration set the stage for many of today's lingering inequalities. As white households left, cities' tax bases shrank, and so did public investment. Waves of urban rioting in the 1960s—a response, in part, to discrimination, and to the neglect of increasingly black cities—further weakened the economies of city centres and led to big rises in spending on policing.

Pandemic unemployment insurance is expiring. This economist has a fix. - Vox

Ioana Marinescu would allow people who've lost jobs to keep collecting $600 a week even after getting a new job.

Arguably the most important economic measure the United States has undertaken during the coronavirus pandemic goes by the unassuming title, " Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation " (FPUC).

It is no exaggeration to say that FPUC is the main force keeping our mass unemployment crisis from becoming a humanitarian disaster. There's only one problem: FPUC is set to expire at the end of July. And given that there is concern from the program's skeptics in the Republican Party that such a generous unemployment check will deter people from returning to work, the chances of the program being renewed are pretty slim.

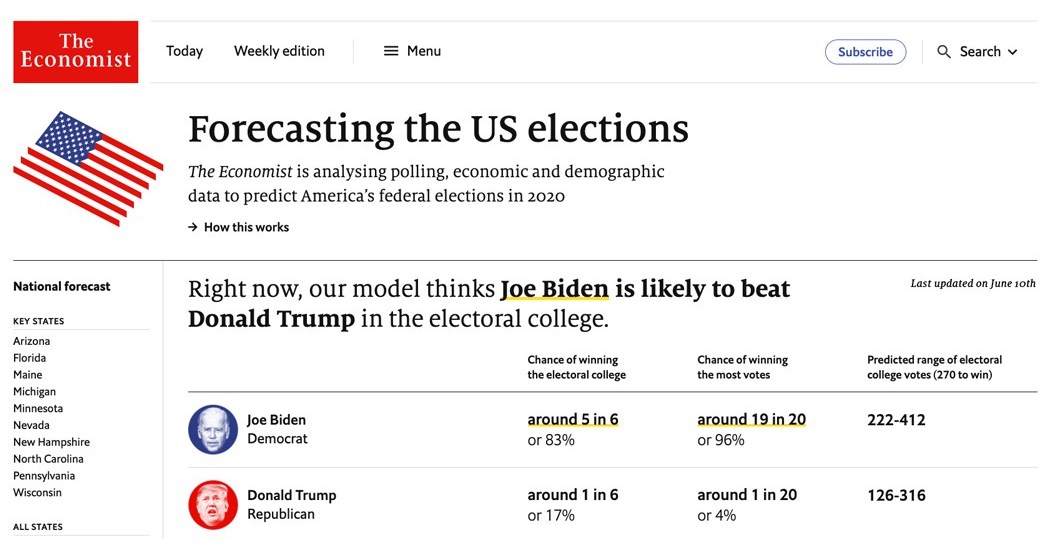

"The Economist US presidential forecast" finds that Joe Biden currently has 83% chance

The model, called " The Economist US presidential forecast", was created by The Economist 's data team with help from Andrew Gelman and Merlin Heidemanns, political scientists at Columbia University . It estimates Joe Biden's and Donald Trump's probabilities of winning each individual state and the election overall.

The Economist 's forecast, the first to be published in 2020 by a prominent news organisation, aims to avoid the flaws that caused models to misfire in the 2016 election. Rather than using equations that merely provide the best fit to data from the past, The Economist 's model uses machine-learning techniques designed to maximise accuracy when predicting the future.

This may worth something:

Hey, big spenders - Germany opens the money tap | Europe | The Economist

Editor's note: Some of our covid-19 coverage is free for readers of The Economist Today , our daily newsletter . For more stories and our pandemic tracker, see our coronavirus hub

On June 3rd the coalition announced a stimulus package worth at least €130bn ($148bn). This follows a €123bn supplementary budget passed in March. Fresh borrowing could reach 6% of GDP this year. Meanwhile, Germany has agreed with France that the EU should issue €500bn in common debt to fund investments in member states hard hit by covid-19. Outsiders who have long despaired of German rigidity find themselves in the strange position of being surprised on the upside.

Charlemagne - Europe's "Sinatra doctrine" on China | Europe | The Economist

At the moment, there is unity only in confusion. Countries are split, both internally and externally. Some have no policies on China whatsoever. Others have a position, but a schizophrenic one, with blasé foreign ministries pulling in one direction, while sceptical intelligence agencies heave in the other. (One diplomat offered a clear-eyed appraisal of his government's strategy on China: "Nonsense".

So far, the EU has solved this problem by treating China as a geopolitical chimera. In 2019 the European Commission labelled China a "systemic rival"—diplomat-speak for an authoritarian brute, with little time for Western norms—as well as a partner on some topics and a competitor on others. Such a frame was "to a degree a cop-out from the start," says Janka Oertel of the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank.

Bello - Does Jair Bolsonaro threaten Brazilian democracy? | The Americas | The Economist

M OST WEEKENDS since covid-19 hit Brazil, supporters of President Jair Bolsonaro have rallied in Brasília and São Paulo. They demand the reopening of a partially locked-down economy, the shutting down of the Supreme Court and Congress and a return to the military rule of 1964-85. A few are armed. In the capital Mr Bolsonaro often joins them, dispensing hugs and handshakes in defiance of health regulations. Neither he nor they wear face masks.

Since Mr Bolsonaro, a former army captain with far-right views, took office in January 2019 many Brazilians have been sanguine about the threat he poses to democracy. Some argue that the country's institutions are strong enough to restrain him. True, the president has stuffed his government with military officers. But they have been seen as a moderating influence. And the demonstrations are small.

Capital Economics: Government won't return to austerity - PropertyWire

In an article written by Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics, she said the attitude of the public is far different to following the global financial crisis, the government's attitude has changed since the George Osborne/David Cameron years, while there is a greater acceptance and confidence in the ability of the government to hold high levels of debt.

Gregory wrote: "Overall, in the coming years there is probably neither the political will nor an urgent need for the government to tighten its belt as much as it did after the global financial crisis.

No comments:

Post a Comment